Beth Immanuel is a friendly and welcoming community. Click here to learn what to expect when you visit.

The Death of Paul Philip Levertoff

At Beth Immanuel, we ordinarily gather on the eve of Rosh Chodesh Av to celebrate the life and legacy of Paul Philip Levertoff. It’s another of our long-standing customs which will not be observed this year for the sake of precautions over the transmission of Covid-19. Rosh Chodesh Av is the first day of the fifth month on the biblical calendar and the beginning of a period of time called “the nine days” which concludes with the a solemn fast on the ninth of Av (Tisha b’Av). The ninth day of Av is the anniversary of the destruction of the Temple. During the nine days, religious Jews observe a variety of heightened mourning customs which include abstaining from meat and wine. For that reason, Rosh Chodesh Av already has a sober quality, but it’s also the yahrtzeit of Messianic Jewish pioneer Paul Philip Levertoff.

Remarkably, Levertoff first fell ill while conducting “the three hours” in church on Good Friday of 1954. He never fully recovered, and he died on Rosh Chodesh Av. The seeming coincidence of the two significant dates reveals the hand of divine providence at work. In his suffering (on Good Friday) and his death (on Rosh Chodesh Av), Levertoff became a symbol for the death of Messiah and the destruction of the Temple, two events which share an inseparable link.

To honor that luminary and teacher, we ordinarily gather on Rosh Chodesh Av, sing some traditional Chasidic melodies together, tell some stories about Levertoff, and read some of his writings. This year, we will not be gathering. Instead, I will share with you the story of Levertoff’s last days as told by his wife Beatrice Levertoff as the account appeared in the missionary quarterly The Church and the Jews (Issues 179-180, July and Autumn, 1954).

Account of the Death of Paul Philip Levertoff in the words of his wife Beatrice Levertoff

As my husband is ill and unable to compile the Quarterly, I am venturing to do it in his stead, so I hope readers will accept my effort with indulgence.

I fear my own illness last year, which lasted for practically the whole of the year until it culminated in my operation, has been the cause of his breakdown. The six weeks I spent in St, Luke’s Hostel for Clergy, in Fitzroy Square, was to him a period of such anxiety and strain that it definitely brought to a head the whole trouble so that on the Sunday after Christmas he showed the first distinct signs of a breakdown. In January he went in to St. Luke’s for observation and spent twelve days there. Nothing specific was decided and he became gradually less and less able to tackle his work each day in the following months, being subject to such frequent attacks of pain and unease; finding no respite eventually so that the doctor advised an operation. All these months he was miraculously able each Sunday to take three services and preach at the old “Leper Chapel” on the hill there, in Ilford, where he had been asked by the wardens and congregation to become their honorary chaplain on the death of Dr. Sparrow Simpson. It was a post he had been unofficially filling for several years anyway, since Dr. Sparrow Simpson had long been unable to fulfill his duties at his great age. He was 94 when he died.

Up to this last Easter my husband had managed every Sunday; and no one guessed at what cost to him in effort, such strengths and power was given to him on each occasion.

The doctor, who examined him on the Thursday in Holy Week, said that if he felt able, he certainly could take the “Three Hours” and Easter Day Services. I was dubious myself; but having seen the weekly miracle of the Sundays, I made no demur. However, the “Three Hours” proved more than he could get through. It is an ordeal for a young, strong man, as he himself often found. He got through two hours without anyone guessing that there might be anything to be apprehensive about. Just as he was beginning the little sermon of the third hour—he had started on it, and then—a pause, a silence. “I am sorry, I must stop for a moment.” He slowly came down from the pulpit and sat in the pew below. In the startled silence one of the congregation near him went to him, and then hurried off for a glass of water for which he had asked. A lady came forward with a little flask of smelling salts. Everyone sank to their knees in prayer. A few moments elapsed; he rose and went back to the pulpit. He made a fresh start from where he had left off—but not for long.

He stopped. “I am so sorry, I can’t go on.” Slowly he descended. Eager hands came to his aid. He was taken into the Vestry. I went out as the congregation again sank to its knees. But, as the Chaplain’s House, from which there was a way into the Vestry, was closed, I had to return. The congregation was now standing as one of the wardens explained my husband’s condition. I walked down the length of the church in a daze, to find my husband sitting white and shaken and a cold sweat on his brow, in the Vestry.

A taxi was called and we took him home. A bowl of hot soup revived him and he sat in the sunny garden for the rest of the afternoon.

He had found the whole congregation in the courtyard of the church as he had come out and he full of apology for not having been able to carry on to the end. They all most lovingly consoled him. Many of them went on to the Parish Church for the rest of the Third Hour.

Time at St. Luke’s

For Easter Day he was at first determined to act. A brother priest, happily free to stand by to help if needful, did in fact officiate because he eventually abandoned the idea of taking it himself. The occurrence on Good Friday had startled him into a realization of his weakness. It was a sore trial to him to be unable to deliver his message to his beloved friends. They sent him loving messages showing how their thoughts were with him and how they missed him, the priest who officiated for him joining in these kind expressions, for he is a friend who has long delighted, when free from Sunday duty himself, to come to the little chapel to worship, and, as he often says, “learn.” This good friend is now, according to his own description of it, “holding the fort” for him.

On the Tuesday in Easter Week my husband went into St. Luke’s with the intention of being operated upon. Two specialists from the University Hospital, which has close connexions with St. Luke’s, saw him. There were consultations, etc., but the weeks went buy and no news of a decision came to us. Eventually we were informed there world be no operation. Then why stay there? My husband longed for home in spite of all the care and kindness for which St. Luke’s is famous. When I approached Matron with this idea she spoke to the doctor and it was agreed upon.

I used to go up each day to see him and take him his letters, etc. He was up most of the day and one day I found he was dressed to go out. Matron met me with this news, said he had desired to go and walk in the lovely garden of the Square; but she had not felt it would be right to let him venture alone, so he should wait for me. We did go to the garden and walked around it, and sat on the seats for half an hour or so. He felt refreshed and was looking forward to his return home. On the Saturday following that Thursday, he was in the garden when I arrived with a brother clergyman who had his operation and was convalescing. They were walking arm in arm. The came together at my call to open the gate to let me in. They walked so slowly I felt quite impatient, thinking: “Why, doesn’t he release the other man’s arm and come quicker to me?” But, alas, it was the brother priest who left my husband and came quickly to let me in. The slow, enfeebled steps were my husband’s! But he was not at all feeble in any other way. We walked around the garden several times and sat down occasionally, but the seats irked his thinly cushioned bones.

The clergyman who walked with him in the garden turned out to be one in whose church a conference had once been held at which the then Bishop of Stepney had presided and my husband had been asked to address them on work among the Jews. Neither had known that the other was in St. Luke’s till they met in the garden. When he had gone in to have tea we remained in the garden, my husband reluctant to return to his room, like a bird released from a cage. My aching feet (I had already walked up from Oxford Street) at last persuaded him indoors to tea. Never have I appreciated tea more!

As we took off his shoes I noticed his feet and ankles were swollen, which he denied stoutly. We spent the rest of the time happily together. Looking forward to his speedy return I went back to Ilford. Sunday was another fine day—Passion Sunday. I was disappointed on arrival to find he had no desire to go out, but felt peevish and ill. We had done too much that last day, I felt.

Monday was no better, but rather worse. He was in bed all day with no wish to get up even.

On Tuesday, the 11th May, I was told by Nurse as I got out of the lift: “Dr. Levertoff is not well today.”

I went into the room. He was sitting on the armchair in his dressing gown looking terribly ill. His voice was weak as he declared how ill he felt.

As I looked more closely at him I began to realize that his lips and ear lobes were blue and his nose white and pinched. I was appalled. I went out to Nurse whose little room was opposite the door of my husband’s room and asked if he could have some brandy. She came in and looked at him and went forthwith to get it. She was so long away to my impatient mind that I went out to look for her. She evidently had phoned down to Matron and was only just then getting the brandy, when I surprised here and made her upset when she had poured. We gave him the brandy.

What happened next I have no recollection. The next thing I do remember was that he was in bed and Matron had come and was saying that the doctor was not in, but the Surgeon was still in. She must have ordered one of the nurses to call him, for suddenly he was there ordering oxygen to be administered. Presently the doctor also appeared and ordered an injection. By and by the ghastly colour changed to normal, but the breathing grew steadily more labored. Hours of which I have no remembrance went by. Matron came up and again and called me out of the room to tell me I must stay the night and a room had been prepared for me.

“How strange this noise is that I am making,” my husband gasped to me. I tried to reassure him by reminding him of the manner in which he had breathed one time when he had had a bad bronchial cold. He accepted it.

The night staff came on. Matron came to bid us “Goodnight.” She had no illusions. She did not expect to see him alive the next morning. She did not say it in words. It was not necessary.

Kneeling by his bedhead Sister asked him if he would not like to take Communion. He gasped a “Yes.”

A Memorable Communion

The Rev. John Pearson had been almost daily visiting his old vicar of St. Luke’s. (The man who had walked with my husband in the garden.) He is an old Ilford “Hospital Chapel” boy whose family had been members there almost as long we had been in Ilford. He didn’t know that my husband was a patient there. It was he that Sister summoned, and he came at midnight, anointed my husband and gave him Holy Communion. My husband recognized him and made all the responses, but with what difficulty. John Pearson said “Good-night” to us. But he, too, did not expect to see my husband again in this life. I was persuaded to go to bed at 2 a.m. when Sister promised not tot leave him and to call me at any sign of a change.

I did sleep a few hours. Around 4 a.m. I went to see how he did, and he was sleeping quietly! From the time when those last rites were administered, he began to rally, Sister said.

Matron was amazed. So were we all. So are we all.

And now he is home again, very weak and emaciated, dependent on injections still to keep at bay the pain. What is before us?

What is before us we do not know; but what we do know is how marvelously blessed we are in friends—Jews and Gentiles—Christian and non-Christian. It seems to us that even His Eminence the Pope cannot have more sincere prayer going up on his behalf than is going up for my husband now, every day. What friends we have, how excellent they are, how they vie with one another in their desire to be of help to us in any way we can suggest! This is a wonderful experience.

For over two years the translation of a book by the late Prof. Adolf Schlatter, which the S.P.C.K. had undertaken to publish, had been delayed interminably, a grievous worry to my husband. Now the Rev. Noel Davey is pushing it on, and what a life-giving joy it was to my husband to get the first sample of the title page and beginning of the first chapter.

How pleasant it is to find our Jewish neighbors anxious to do for us anything they can. Some of them came to visit my husband in the Hostel, all of them sent message of love and respect. From so many unexpected and even strange quarters have the proofs arrived to comfort the invalid with the knowledge that his years in the service of his beloved Master have not been spent in vain. Times like these bring to light the fruits so long hidden. Maybe that is one of the objects our Lord has in mind in bringing about this period of anxiety.

To those of the readers of the Quarterly who had no knowledge of my husband’s illness may I ask for your prayers on his behalf. To those who know, we send our heartfelt thanks for your prayers and most kind sympathy.

I am including in this issue a very interesting article, which has appeared in an American Jewish magazine, which contains a great deal of what my husband has always said himself to Jews on this subject. It is so well expressed that I leave it to speak for itself. It has given my husband much satisfaction to find someone far away and a stranger to him having the self-same standpoint teaching just what he has been teaching all these years in the wilderness, as it has often seemed.

Farewell

In July last I prepared the Quarterly for my husband who in bed watching me do it and giving me his counsel, ill though he was. Even then it did not seem likely that by the end of the month he would have gone out of that racked body from which he was, at that time, longing to be free. On the 31st of July, in the very early hours, saying to me his last words, which were “Good-bye,” he left me to go with glad relief from pain, into the waiting outstretched arms of the Lord he loved so utterly. There were such volumes of prayers going up for his recovery, when I was preparing that last number under his guidance, and he felt that “life was sweet” still. When the Quarterly arrived he took a number to read. He was still sitting in the garden in the sunshine, and for the moment free from acute pain. I left him to see to some household task. When I came back he looked at me sadly, and said: “I find it so difficult to read.” “Why, dear?” I asked, “Can’t you see it properly?” “Oh yes, I can see; but somehow I take so long to read it. I have only managed to read this one page all this time.” He looked so puzzled, not understanding his failing powers of concentration. Gradually he could not even bear being read to. It was too much for him. Then he began to say; “This is no life.”

His mental powers never died. His thoughts were constantly with heavenly things, the things of the earth became of no moment. In delirium he spoke only of spiritual things, of God, of his desire to express adequately his love for God. To everyone who came to see him he soon turned every talk to such matters. At such moments he would rally to such an extent that, even to the last, those who visited him could hardly grasp the frail hold he now had on earthly life. He had faced death long before, when he went to the Hospital; we had faced it together and that had not to be gone through again.

There came a moment when he asked me not to pray for his recovery, begged me to ask all the friends to desist. Then, when he still lingered, he wondered why God kept him here, he seemed to see no reason for it. I, oddly, had to turn counsellor to him. I suggested that to dies was easy; to live was the thing that needed courage and endurance. Probably God had some task still for him, if it was only to teach him this last difficult lesson of physical suffering of his Lord. He accepted it in all humility. He set out to live again in all his pain—and how he bore it all—so gallantly—he who hated and feared pain so much! He never complained, only wondered at it. And there came several to assist him in these his last days, and he was given such power of mind and speech that they were astonished, and oh ! so blessed. So there was truth in what I had so gropingly said in my effort to comfort him. Jews and Gentiles, Christian and otherwise, were helped in ways that the have told me they will never forget. He was permitted to give them something out of his own deep stores—in life, and death.

The word “death” comes haltingly to my pen in connection with him. Only to his racked body does this word apply; and, even then, that body recovered its loveliness so marvelously as to move us all. All trace of pain left him and he smiled, serene and sure in a way that convinced all who looked on him that he was not just at peace, resting from his pain, but had attained his heart’s desire—to magnify Him as he really would wish. One Jewish man seeing him, murmured brokenly; “He was a Saint.” His great learning was all forgotten in his goodness, his loving-kindness, his wise, good heart. I had always been proud to be chosen to be companion of such a rare, great scholar and rejoiced in the appreciation accorded it; but now I rejoice oh so much more to have had an even greater privilege.

Thirty Years Work

Looking through old Quarterlies the progress in the work can be seen which, at the time, seemed even non-existent. A work like this is so different from any other mission work among any other people. Missionaries go out to lands where the Christian faith is unknown—where religion even means some barbaric rites full of fearful superstitions. Even when missionaries have gone to attempt to teach the Christian faith in lands where there is an old tried religion, with a civilized basis, as in the Far East, the problems, though great and difficult, have no resemblance to those that confront anyone who goes to try and influence the Jewish people in an attempt to preach Christ to them. Here the missionary is up against more things than mere prejudice. The roots of misunderstanding go down so deep into the past.

Beginning in Jerusalem, 1954 years ago. And the Church, alas, has promoted this misunderstanding from century to century ever since, even while, at the same time, trying to reach the Jewish people to convert them to the Christian Faith. A strange and amazing state of affairs. Even in the writings of St. Paul and the Apostles we see how from the outset, when the communities of Christians grew, and Gentiles joined them, all sorts of ideas and teachings crept in the contrary to the real true Faith, and quarrels and intrigues spoilt the spirit of the congregations. No wonder that when the original Jewish-Christian Church was swamped by sheer numbers as time went on, the whole Church seemed an alien thing to the Jews. And the Jews became to the Gentile-Christians also mere aliens, whom they could not understand, but longed to force into the Church, as they would not be persuaded.

The savagery of the Christianized barbarians of the Middle Ages in Europe widened the gap, printing on the Jewish mind such a picture of “Christians” that has not worn off to this day in many Jewish circles. Ghetto life added its quota to this sad state of things, for there, in the Ghetto, the Jewish people lived a life of isolation so completely removed from the world outside—a world which, as it seemed to them, of riotous living, extravagant and obscene, of people only to be feared and hated, whose one idea towards the Jews was to persecute them and rob them.

The Gentile-Christian world meanwhile viewed these Jews as strange, a people to be feared obscurely, around whom legends had arisen, so ugly, that they were moved only to persecute them out of sheer fear. And all this in “Christian Europe,” where all the beautiful Cathedrals were rising up, in which all the passionate love and sorrow of the Jewish Christ was proclaimed, and Jewish psalms were sung, and Jewish scriptures were read and honored. How could members of such a community reach their Jewish neighbors? Neither could enter into the mind of the other without such clearing out of prejudices and misunderstanding as seemed impossible to accomplish. But, as with Abraham of old, now and then a special light was given to some Jew to make it possible for him to penetrate beyond all this accumulation to the Truth; and from time to time the same kind of light was given to some Gentile to act in the same fashion. To obtain this enlightenment is a great privilege., This was the privilege given to St. Paul, so miraculously singled out for the work.

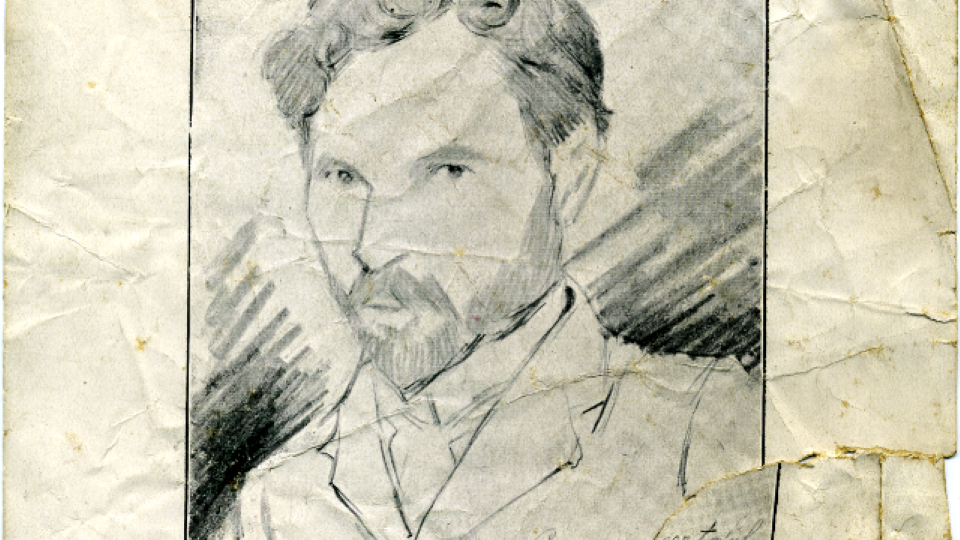

Levertoff’s Journey

Paul Levertoff was brought up in a Hassidic atmosphere. This means that Judaism was a spiritual thing, not just a legalistic religion. When, by chance, this child one day found flying about the street of the little Russian town some leaves torn from a book that had been printed in Hebrew, he was amazed to read something that seemed to him Hassidic; but so strange, for it related in detail an account of the Messiah who had been crucified. It was parts of the Gospel according to St. John. Young as he was he feared to show it to his father; but he pondered it in his heart and long years after when he read again those very words in Delitzch’s Hebrew New Testament they brought conviction and he gave himself, heart and soul, into the keeping of the Messiah Jesus with such enthusiasm that nothing could restrain him.

With the impetuosity of youth he left this home and his people there, because he could not prevail upon them to agree with him at once. What was now to him so clear did not so appear to his parents. This filled him with such anguish that he fled, penniless. In later years he regretted this impetuosity. He often felt that if he had been wiser he would have gained his father, for he realized how near the Kingdom he was. He dedicated one of his books to his father – “an Israelite in whom there is no guile.” To his father, his grandfather, and to his mother’s uncle, The famous Rabbi Shnoer Salman, he felt he owed his own preparation for, and understanding of the teaching of Jesus. In his last hours he talked with them, and assured me that they were now “of the Kingdom” and awaiting his coming.

Levertoff’s Life Work

Search for knowledge concerning everything related in the New Testament obsessed him. It drove him to Palestine to study Aramaic, and to see for himself the very places where the Sacred Feet had trod. All through his life henceforth he had one aim--to know and to spread that knowledge among all persons he contacted, but especially among his own people. Joyously he went travelling in Europe and Asia Minor, and everywhere he won men and women, young and old, to listen, to ponder, to learn and understand. Wherever he went he was remembered by those who met him as I know from personal experience. He was remembered with love and blessing. He was feared only by those who feared to be convinced. In the Quarterly of April, 1927, he is writing “The readers of the Quarterly will recollect how, at the commencement of my work at Holy Trinity, Shereditch, the Jewish Press honored me and my work – with much criticism, and warned the Jews to beware of a person with such fell designs upon them!”

He was working by this time for the London Diocesan Council, or the E.L.F.J. as we more familiarity called it. Dr. Frere, of Mirfield, later Bishop of Truro, had drawn the attention of the Bishop of London, the late Winnington Ingram, to Paul Levertoff, who was then Sub-warden of St. Deiniol’s Library, Hawarden, as a desirable person to carry on the work of the Council which had originated with Father Rosenthal. The work was about to be discontinued as there was no one to carry on. The Bishop of Stepney, the Rev. H. Moseley, later Bishop of Southwell, was bidden to ask him to come to London. He came, wondering what could such a request portend. He accepted the post of Director of the work with a carte blanche, as no one had any ideas concerning such a work, for the original work had completely vanished except for a Quarterly and some women workers allotted to churches in the East End in Jewish neighborhoods. But as these women had no idea what was expected of them, they became merely workers for the parishes paid and by the E.L.F.J.! Paul Levertoff could not even start from “scratch” but had to clear away the tough weeds before being able to begin.

The idea of a Jewish-Christian Church was born, however, with a Jewish-Christian liturgy. A church was a prerequisite for this work, but that was not a success because it was situated in an inaccessible district. During all the 30 years of this work the one thing he begged to have was a church in a central position, a live church where he could create a living link between Jews and Gentiles, as he had no wish to segregate them. His ideal was to use alternately a Jewish-Christian liturgy and the usual Anglican services and attract people to both. St. George’s, Bloomsbury, did, to some extent, enable him to carry out this idea through the loving aid of his dear friend, the late Father Roberts, who was for so many years Rural Dean and Vicar of that church.

At St. George’s, Bloomsbury, there gathered a congregation on Saturday mornings for years, culled from all ranks and from many countries. Every part of Europe, at on time or another, was represented by someone, Jewish or Gentile. From the several parts of the American continent, from India, from the Colonies, someone would turn up.

From Palestine, Israeli, as we now say, there came many young people, some of them students from the University. Once, two people who lived in that country and had long desired to make one another’s acquaintance, at last were to find one another in St. George’s, Bloomsbury, one Saturday morning, to their own surprise and delight!

Words About Dr. Levertoff

What years of activity, of ups and downs, of tragedy and comedy, these thirty years have been! How difficult to write about in terms of “scalps.”

They are gone, and what is the verdict of time.

Here are extracts from the letters received after he has gone to his reward: —

From the Secretary of the Jewish Historical Society:

“I was deeply grieved to hear of the death of your husband and I would convey to you on behalf of the Honorary Officers and the Council, as well as on my own behalf, the profound sense of loss which we feel in his passing. He rendered great services in his endeavor to create understanding and love between Jews and Gentiles, and his memory will long be cherished by all.”

From the Greek Archidandribe:

“In presenting my sincere condolences I desire to assure you that his work and his memory will remain alive in us for ever.”

From some of our Ilford Jewish friends and neighbors:

- “Dr. Levertoff was revered and respected in Ilford as few other men have been and his passing will leave a very considerable void. He will always be remembered for his essential goodness and his kindliness to all those who had the great privilege of knowing him.”

- “We feel that as time passes you will derive more and more consolation from the high esteem in which your husband’s noble character is held. His deep scholarly knowledge, his meekness and understanding impressed everyone who knew him.”

- “I cannot refrain from expressing my feeling and admiration for the man I knew so well and the regard I felt towards him. He was for me the embodiment of a noble soul, the truest Jew I ever met. Although some of his fellow Jews misunderstood him and often vilified him, yet he never bore any malice. As a brilliant scholar of Hebrew, few were his equals, and as a Talmudist of eminence he ranked among the greatest. Of him it can truly be said—he was an Israelite in whom there is no guile.”

- From the young people he rescued from Nazidom a few of the messages:

- “Perhaps you will derive some measure of solace from the knowledge that Father’s life-work will remain living inspiration and example to all of us to whom he became true father in an hour of supreme need.”

- “We were stunned by the terrible news of Father, whom we loved so very much. You know how much we admitted and regarded him, quite apart from how much we owe him. Without him—where would we be now?”

- “The sad and unbelievable news of the passing away of dear, dear Dr. Levertoff has reached us here (Switzerland) and my heart is full of love and gratitude for you and your most wonderful and saintly husband… In the hearts of my family Dr. Levertoff will always retain a high place, and our only regret will be that we have not been able to show ourselves really grateful enough for us all. Please believe me if I say that we feel very humble at the thought of his greatness.”

- “There has been in my life no man who equaled Dr. Levertoff in his saint-like kindness and love to all his fellowmen. I wish to re-affirm my permanent gratitude to the man who has done for me more than anybody else and to whom, in all probability, I owe my life and all I am.

- “The thought struck me whether perhaps all the boys of ‘The Hostel’ could in some little way help in some of the Doctor’s works towards helping others in distress. To help, somehow, somebody to best of our ability, in memory of the dear Doctor.”

- And another from an older man than himself:

- “I shall never forget his Christian humanity which helped me so much in my thorny way to conversion. When one got in touch with Dr. Levertoff one felt that there was a sense of holiness in him, that near sense which marks Christian religion as the real source of life, and is ultimately connected with the experience of the source of life, and is ultimately connected with the experience of the mystic—it sems to me—is the vital part of Jesus Christ’s Message. He has lived his long life in full, in an active and spiritual Christian conception of God.”

- “His was a great work here on earth. You can think of him as alive and rejoicing in the fruits of his labors.”

- “He taught us the perfect dignity of real humility.”

- “His gentleness, learning and sanctity marked him as a Great Man,” writes the Archdeacon of Southend, and the Bishop of Barking writes: “He lived a life of great usefulness to so many people, and in later years earned the gratitude of the people of this Diocese for his help at Ilford.” And the people? — “We all loved him so much and were so grateful for the way in which he helped us there. Ilford, and the Hospital Chapel in particular, have suffered a great loss. Truly he died in harness, I feel sure that would have been his wish—to labor in his Lord’s service to the last.”

- One of his “sons” among the young men in the Hostel at Holy Trinity, shall end with his verdict—“We, at the Hostel, always regarded the Doctor as a present-day Saint, a man not of this cruel world, but of the Kingdom”; and the fellow-priest who writes: “The whole Church owes him a great debt—it will be all the poorer without him.”