Beth Immanuel is a friendly and welcoming community. Click here to learn what to expect when you visit.

Is Rosh Hashanah the New Year?

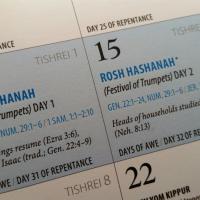

The Torah commands that we observe a certain holiday on the first day of the seventh month. Scripturally, it is given two similar names: yom teru'ah (Day of Blasting/Shouting) in Numbers 29:1 and zichron teru'ah (Remembrance of Blasting/Shouting) in Leviticus 23:24. Jewish tradition refers to this day as Rosh HaShanah, which means "Beginning (lit., 'head') of the Year." But how can the beginning of the year occur in the seventh month? Didn't God command that the new year is to begin in the springtime? In Exodus, we read,

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, "This month shall be for you the beginning of months. It shall be the first month of the year for you. Tell all the congregation of Israel that on the tenth day of this month every man shall take a lamb according to their fathers' houses, a lamb for a household." (Exodus 12:1-3)

As we can see, the springtime month of Passover is to be considered the "first month of the year." If this is the case then we should consider the new year to begin on the first day of the springtime month--not in the fall.

Watching the Ball Drop

But we should ask: what do we mean by "new year"?

Modern civilization considers the new year to begin on January 1. But this date and the numbers of our years are quite arbitrary. The date of January 1 was based on the ancient Roman civil year, probably linked to the winter solstice. Medieval Christians noted that it was eight days after December 25 and thus corresponded to the traditional date of Jesus' circumcision. Our year number was originally intended to tie to an actual historical event (the birth of Jesus), which was miscalculated. But it doesn't really matter that it was miscalculated as long as everyone agrees on it, so that it can serve as an arbitrary point of reference.

January 1 has lost its significance. Today people seem to simply accept it as the day when the year changes - as if ontologically, the year is 2010. Civilization almost treats the year number as a built-in feature of the created order.

But it wasn't always this way. Throughout history, each civilization had their own significant events that they used as a frame of reference to mark the passing of time. The most common event was the inauguration of kings. This is how the Bible usually marks dates:

But by the twenty-third year of King Jehoash, the priests had made no repairs on the house. (2 Kings 12:6)

During the exile, there is no king, so the prophet Ezekiel marks time by the exile itself:

In the twenty-fifth year of our exile, at the beginning of the year, on the tenth day of the month, in the fourteenth year after the city was struck down, on that very day, the hand of the LORD was upon me, and he brought me to the city. (Ezekiel 40:1)

This should point out to us that the mere question "What year is it?" does not make sense without a specific context. A better question would be "How many years has it been since such-and-such occurred?" Likewise, asking "When is the new year?" is like asking, "When is the anniversary?" The anniversary of what?

Think of it this way: when people ask how old you are, you will calculate the answer based on your date of birth. For you, your birthday is your new year. Other times, it makes sense to lump people of similar ages into the same group. When we ask a child, "What grade are you in?" the beginning of the school year at the end of summer becomes the calculation date--the new school year. In the context of school, it is not at all uncommon to refer to September, October, November, and December as "the beginning of the year."

So the number of the year and the exact date that it switches on depend on what information a person is seeking. Outside of any other context, we might suppose that we are talking about the anniversary of creation. But the Bible does not tell us what time of year the world was created. When Exodus 12 declares the springtime month the "first month of the year," it does not tell us that it was the month of creation. The only thing it tells us is that it was the month of the exodus.

The predominant Jewish opinion is that the sixth day of creation occurred on the first day of the seventh month, and thus it is the anniversary of the formation of Adam, the first man. Another Jewish opinion is that this occurred in the spring. Regardless, the seventh month is a new beginning.

The Agricultural Cycle

In ancient civilizations--Israel being no exception--one of the most dominant yearly cycles was the agricultural year. The Gezer calendar, for example, is a paleo-Hebrew inscription from the tenth century BCE. Even though it dates to centuries before the Babylonian exile, it describes each month of the agricultural year, beginning with the fall and ending in the summer.

For the ancient Israelites, the agricultural cycle was unavoidable. One plants in the winter and harvests that planting through the summer. This cycle is a fact of nature, determined by the God-ordained seasons and climate.

In regards to the agricultural cycle, the Bible instructs that every seven years there is to be a Sabbatical year in which the land receives its rest:

For six years you shall sow your field, and for six years you shall prune your vineyard and gather in its fruits, but in the seventh year there shall be a Sabbath of solemn rest for the land, a Sabbath to the LORD. You shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard. You shall not reap what grows of itself in your harvest, or gather the grapes of your undressed vine. It shall be a year of solemn rest for the land. (Leviticus 25:3-5)

As you can see, this seven-year cycle is entirely based on the agricultural year. To take one year off from planting and harvesting, one would have no choice but to begin in the fall, when the previous year's harvest is completed. Thus, each of those seven years must be counted from harvest to harvest--not from spring to spring.

As we read further, we find that this seven-year agricultural cycle is a part of a larger fifty-year cycle culminating in the Yovel (Jubilee) year:

You shall count seven weeks of years, seven times seven years, so that the time of the seven weeks of years shall give you forty-nine years. Then you shall sound the loud trumpet on the tenth day of the seventh month. On the Day of Atonement you shall sound the trumpet throughout all your land. (Leviticus 25:8-9)

Notice how this cycle of forty-nine years ends in the seventh month. But why would the Torah insist on referring to the time of harvest as the "seventh month," if it is legitimately the beginning of the year?

The Year's End

We find similar language when we read about the three pilgrimage festivals, particularly when they are described in view of the agricultural year:

You shall keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread, as I commanded you, at the time appointed in the month Abib, for in the month Abib you came out from Egypt. All that open the womb are mine, all your male livestock, the firstborn of cow and sheep. The firstborn of a donkey you shall redeem with a lamb, or if you will not redeem it you shall break its neck. All the firstborn of your sons you shall redeem. And none shall appear before me empty-handed. Six days you shall work, but on the seventh day you shall rest. In plowing time and in harvest you shall rest. You shall observe the Feast of Weeks, the firstfruits of wheat harvest, and the Feast of Ingathering at the year's end. (Exodus 34:18-22, emphasis added.)

What is spoken of here as the Feast of Ingathering (Chag Ha-Asif) is known elsewhere as the Feast of Tabernacles (Chag Ha-Sukkot), which is observed in the seventh month. Similar language for Sukkot is used in Leviticus:

On the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when you have gathered in the produce of the land, you shall celebrate the feast of the LORD seven days. On the first day shall be a solemn rest, and on the eighth day shall be a solemn rest. (Leviticus 23:39, emphasis added.)

This passage raises two questions. Why is a holiday in the seventh month called the "end of the year"? Also, why is the holiday of Sukkot called by the unusual name "the Feast of Ingathering" in this passage?

All of the biblical holidays are multifaceted. Not only do they each commemorate events of redemption that the nation experienced, but they also coincide with the agricultural cycle. There are other things we can notice that is unusual about the wording of this passage.

First, notice that the Feast of Unleavened Bread is mentioned without speaking of the Passover lamb sacrifice. Instead, the passage draws attention to the name Abib (or "Aviv"). Normally, the Torah uses numbers, not names, to describe the months. The word Aviv is the Canaanite name of the springtime month, and it means "ripe ears of grain." By using this terminology, the Torah is focusing attention on the agricultural cycle.

What follows are instructions regarding the firstborn young of animals. Once again, this ties to the seasonal cycle. Next, the commandment to rest on the Sabbath is reiterated, but this time it is clarified that the Sabbath remains in effect even during times of plowing and harvest--another agricultural cue. When the Feast of Weeks (Shavu'ot) is mentioned, the Torah includes the note that it is "the firstfruits of the wheat harvest," again emphasizing the agricultural connection.

This explains why the Torah would refer to the holiday of Sukkot with this unusual term, the "Feast of Ingathering." Although a sukkah ("tabernacle") is in fact a harvest hut--a makeshift shelter from the sun used during the harvest season--the Torah also connects the sukkah to the exodus from Egypt (Leviticus 23:42-43). By referring to this holiday as "ingathering," the Torah emphasizes its relationship with the agricultural year.

This also explains why a holiday in the seventh month would be called "at the end of the year." It is the end of the agricultural year. The Hebrew word translated "end" by the ESV is tekufah, which has the sense of cycling or turning--making a complete circuit. It is not only an end, but a new beginning.

The Seventh Month

We can now return to our question about why the Torah would call the beginning of the agricultural year the "seventh month."

The agricultural cycle of planting and harvesting, which completes its cycle in the fall, is not pagan or Babylonian. It is of divine origin and perceptible through nature in every culture.

In the instruction to number the months in Exodus 12, the agricultural cycle is not in view. Rather, it is the redemption from Egypt. By numbering the months beginning with the month of the Exodus, we remember that this is our beginning. Everything hinges on that miraculous event.

As the agricultural cycle renews, one might be tempted to forget that everything we have comes from HaShem. If it hadn't been for the redemption from Egypt, we would have no fields or vineyards or orchards or herds or flocks. By acknowledging the beginning of the agricultural year as six months away from the redemption, we stay anchored in the reality that as we engage in labor and reap its benefit, we are doing so as servants of our Creator and Redeemer.